Announcements

Drinks

ESG in 2022: filling the disclosure gap; can carbon pricing address climate-reporting complexity?

Improved disclosure by companies is vital to help market participants assess ESG impact.

The problem is that expanded accounting and regulatory frameworks to simultaneously serve multiple stakeholders turn out to be lengthy, costly, and insufficiently orchestrated.

“The big question for 2022 is therefore how quickly standard setters can agree on binding standards for non-financial disclosures, if at all. Progress in this area is vital, not at least because other flagship projects such as the implementation of the EU’s SFDR and taxonomy depend on it,” says Brandenburg.

“A complementary – if not more effective - approach is to ensure that negative externalities are directly reflected in financial statements through, in the case of greenhouse gas emissions, better and more transparent carbon pricing,” he says.

The planned expansion of the EU’s ETS to transport and buildings will widen the reach of carbon pricing in the EU as will the carbon border adjustment mechanism which proposes a levy based on the carbon-content of selected imports to the EU.

Strikingly, the widely acknowledged ESG disclosure gap is neither due to lack of effort nor rhetoric. Numerous disclosure frameworks at global, regional, and national levels have been available for many years, and most listed companies maintain that they adhere to at least one of them.

Scope’s non-exhaustive list identifies at least 10 frequently cited standards that cover various aspects of ESG-related financial and non-financial information. Yet, confusion reigns because disclosures are mainly qualitative and at times trivial, while quantitative disclosure remains voluntary and difficult to compare

In the meantime, Scope sees two main trends shaping the debate surrounding corporate sustainability during 2022: the regulatory and policy-making focus will remain on tackling climate-related issues; ESG research will increasingly re-emphasise impact assessment over ESG-linked risks.

“This is important from a credit perspective,” says Brandenburg. “Fixed-income investors typically neither take part in the financial upside involved with large-scale climate investments nor are they in a position to bear the associated project and technology risks. However, bondholders require assurance that their funds refinance assets in line with ESG values.”

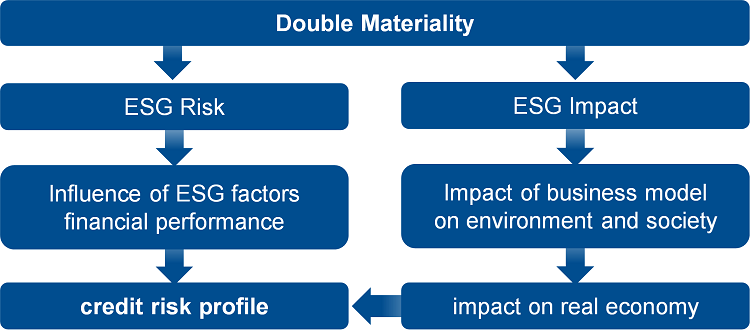

ESG impact and ESG risk analysis are converging over the long term because one actor’s ESG impact drives another actor’s ESG risk and vice versa,

This applies especially for the systemic risks posed by global warming. Large corporates and regulators increasingly focus on indirect reporting of emissions accruing in the value chain (“Scope 3”). Accounting for supplier footprints and emissions in final consumption aligns directly exposed industries (“risk”) with their neighbouring sectors (“impact”).

This “double materiality” of ESG risk and ESG impact will shape the debate over disclosure and accounting materiality but also influence discussion of how best to assess the ESG profile of an investment and its classification, for example, under a taxonomy such as the EU’s.